|

March 31st |

|

May 26th

John started his presentation with a discussion of planning your processing of a log to give you a balanced grain in your finished piece to reduce uneven warping as it dries down.

Live turning demonstration went from green wood log to finished bowl in one turning.

Turning to a consistent wall thickness of one quarter inch or so was suggested to be one way to reduce the chance of the piece cracking as it dried down.

Warping can be minimized by turning to a thin wall thickness and balancing the grain of the piece. Minimized but

not eliminated, a green wood turning is going to warp as seen here in some examples passed around durning the presentation.

|

|

May and June

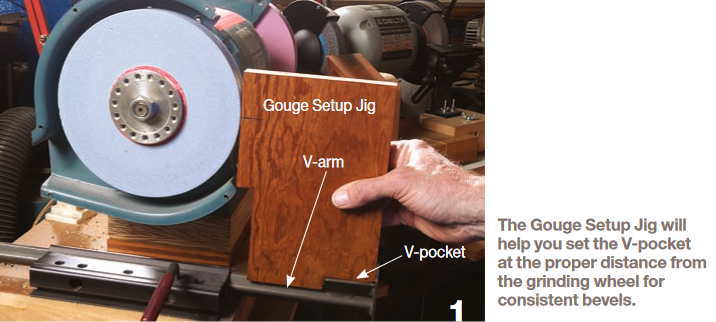

Principle 1: Tool Sharpness

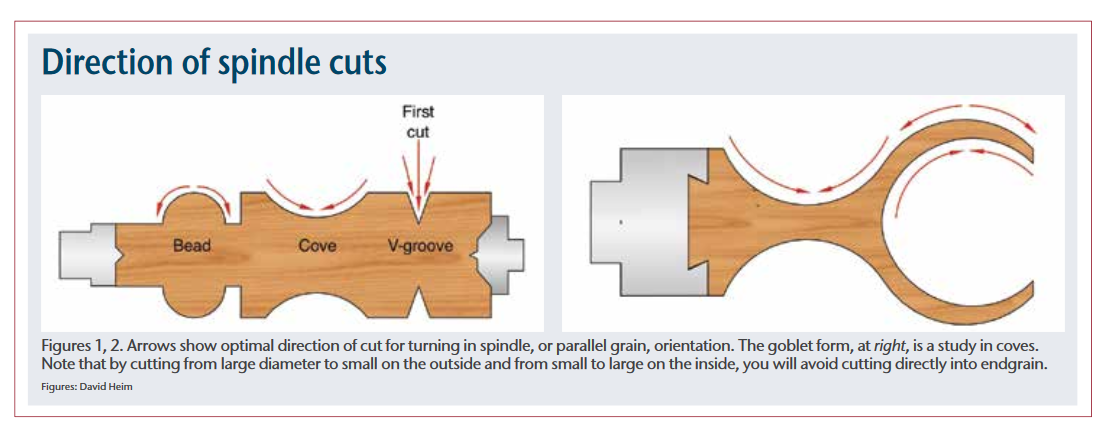

Principle 2: Grain Direction

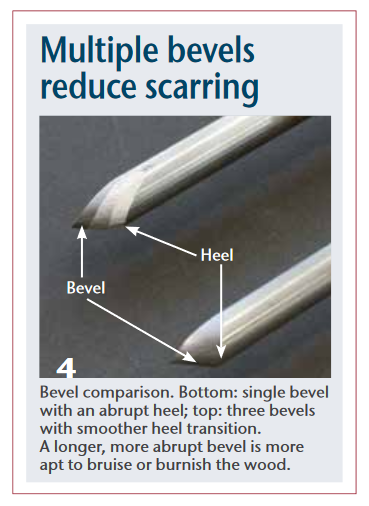

Principle 3: Bevel Angle and Length

Principle 4: Bevel Contact

Principle 5: Cutting Arcs

Principle 6: Shavings

Principle 7: Tool Clearance

Principle 8: Amount of Cutting Edge Applied

Principle 9: Feed Rate

Principle 10: Tool Stability |

|

July 28th

Lyle led the club through a veiwing of two projects from the Nick Cook DVD

The first project selected to view and discuss was a platter to see the techniques Nick used in side grain orientation

The second project selected to view and discuss was a French rolling pin to see how Nick approached spindle grain orientation Nick Cook is a full time production turner producing a wide variety of gift items, one of a kind bowls and vessels. In this DVD, Nick demonstrates how to create nine different items that are useful in the kitchen. Projects include: a rolling pin, spurtle (stirring stick), plate, honey dipper, coffee scoop, wine stopper, an amazing salt urn and a pepper mill. |

|

October 27th |

|

Guest presentor Joe Grimm demonstrates the techniques he uses to create hollow forms. Joe working on the outer surface of the hollow form. Although the techniques used here were fairly standard for a spindle-orientation project the very dry cherry burl was very tough with some soft spots and voids which is why Joe used a heavy bowl gouge for most of this work. Joe turned the piece around and started the hollowing operation next starting with traditional tools and then using carbide and scraper hollowing tools. Most of the work on the neck area was done with the bowl gouge. A large drill but was used in a chuck held by the tailstock to remove the core of the vase and establish the overall depth as a guide for his efforts. Judging progress during hollowing effort involved stopping the lathe, clearing the shavings and inspecting by eye.> Again the tough cherry burl with its soft spots, bark inclusions and voids made this an interesting experiment!

Finished piece, not completely finished but as far as we could go with the time permitted. We had a good crowd and an interesting discussion. Great presentation Joe! |

|

November 17th |

|

Mark Behrends presented a well-prepared and comprehensive discussion on sanding techniques, tools and materials. Mark used a wide variety of the may types of sandpaper and mesh commonly used by club members. Mark also demonstrated several approaches to power sanding and hand sanding with a focus on safety and getting a great finish on the wood. From his experience and expertise in turning a bowl from a green log in one session Mark was able to answer a number of questions on how he sands these pieces as they warp into their final shape. We had enough questions and interest in the milk paint finish technique that Mark uses on these bowls that the club will try to schedule a 2017 presentation to focus on this topic. A great presentation and very good question-and-answer with the crowd. |

|

December 15th |